Hail, fellows, and well met!

During the course of your individual work on this project, you will need to complete a series of challenges relating to your social status and your relationship with the rest of the feudal world of 1207 CE. At this point, you should have completed the background work to better understand the geographic world of the High Middle Ages in western Europe in the 13th century. You should have also decided where your fiefdom is located, your fief’s motto and heraldic colors, and its name. You’ll need to keep that information handy, as you will be using it again during the course of these challenges.

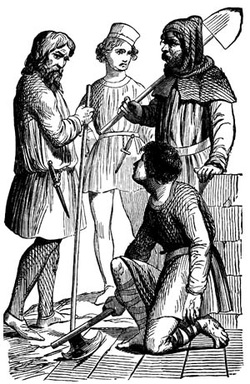

The social world of the feudal High Middle Ages was one which was intensely hierarchical; every person in society had a role, and there really wasn’t a lot of movement within the various divisions of society. If you would like a detailed explanation of the medieval social hierarchy or simply want more information about your social position in general, I recommend watching the following video on the origins of the European social order which persisted up until the French Revolution of 1789 CE. You’re not required to watch this, but it is good information, and might prove helpful in your future work:

During the course of your individual work on this project, you will need to complete a series of challenges relating to your social status and your relationship with the rest of the feudal world of 1207 CE. At this point, you should have completed the background work to better understand the geographic world of the High Middle Ages in western Europe in the 13th century. You should have also decided where your fiefdom is located, your fief’s motto and heraldic colors, and its name. You’ll need to keep that information handy, as you will be using it again during the course of these challenges.

The social world of the feudal High Middle Ages was one which was intensely hierarchical; every person in society had a role, and there really wasn’t a lot of movement within the various divisions of society. If you would like a detailed explanation of the medieval social hierarchy or simply want more information about your social position in general, I recommend watching the following video on the origins of the European social order which persisted up until the French Revolution of 1789 CE. You’re not required to watch this, but it is good information, and might prove helpful in your future work:

|

As a peasant, your primary duty is to see to obey your local master and work to provide yourself and your community with a plentiful harvest. You might also be conscripted to serve as a foot soldier in times of war, or to serve as unskilled laborers if there’s something that needs to be built or repaired. This is a social and political order based around reciprocity and loyalty, and while your life may be very humble, that in no way means it is without its joys and moments of pleasure.

Peasants’ Challenge First, please download the Peasants' Challenge if you don’t have your hardcopy of the handout in front of you. As your first challenge, you will need to:

|

Medieval Naming Conventions

First, a bit of excellent background information from “Common Naming Practices: Being a Brief Guide to Bynames in the Major European Languages and Cultures” by Walraven van Nijmegen (2003).

Parts of names: In the majority of European cultures, personal names contain two basic kinds of name element, given names and surnames.

The given name is so called because the family bestowed it upon the child at birth or christening. Given names may be traditional names in the culture, saints, heroes, honored relatives, and so forth. The pool of given names differs from culture to culture. For example, Giovanni is the characteristically Italian form of John, the name Kasimir is almost uniquely Polish, and use of the name Teresa did not spread outside of Spain until very late [in the medieval period]. Because given names vary so much by place and period, describing them adequately is beyond the scope of this article. However, many collections of given names are available on-line at the Medieval Names Archive.

Surnames are the second major category of name element. Today’s surnames are inherited family names, but for most of [the medieval] period, surnames were not inherited but chosen to describe an individual and distinguish him or her from other individuals with the same given name. Such surnames are called bynames.

Byname origins and meanings: To understand how bynames originated, image that you lived in Amsterdam around 1300. You are listening to a friend sharing local gossip about a man named Jan. Now, one out of every ten people in Amsterdam is named Jan, so how will you know which one your friend means? Is it big Jan who lives at the edge of town? Jan, the butcher? Jan, the son of Willem the candlemaker? You need additional information about who Jan is to identify him, and that is what a byname does.

Bynames show up all over Europe in four basic flavors:

* patronymic – byname that identifies a person’s father. There are other bynames of relationship, but the patronymic is by far the most common of these in Europe.

* locative – byname that identifies where a person was born, lives, or has an estate. These can be formed using a proper place name or a generic feature of local geography.

* occupational – byname that identifies a person’s trade or occupation.

* nickname – byname that describes an individual’s personality, character, dress, physical appearance, or other outstanding trait. These are not chosen by the bearer of the nickname, but by friends, family, neighbors, or enemies, and becomes known through frequent use.

I strongly recommend that you read over the rest of the article, because it does an excellent job of explaining how naming conventions traditionally worked in the medieval period for most people. Additionally, you might find the following sites useful in order to better understand the social order of the medieval world and the various trades your individual might participate in:

You’ll want to make sure that the given name you select is appropriate for the region in which your fief is located, so pay attention to the potential for Germanic, Latin, Celtic, or Norse roots. There’s an excellent site at “Medieval English Names” which might be useful to you, even if your fief isn’t located in England. At any rate, here is a collection of fairly common given names from the 12th and 13th centuries, separated by gender:

Male Names

Adam, Gervase, Gilbert, James, Louis, Ralf, Ademar, Geoffrey, Gerard, John, Walter, Warin, Amaury, George, Bernard, Matthew, Jan, Wulfirc, Alfred, Guy, Nicholas, Lucas, Thomas, Richard, Bernard, Hubert, Aldous, Roger, Simon, Reginald. Charles, Ernis, Henry, William, Percival, Roland

Female Names

Agnes, Agatha, Alice, Avice, Aldith, Astrid, Eva, Beatrice, Elizabeth, Mary, Martha, Philippa, Gilia, Helen, Sybil, Sadie, Lavinia, Isabella, Scholastica, Julia, Margery, Margaret, Molly, Muriel, Joyce, Cecily, Urith, Isolde, Winifred, Grace. Ann, Jane, Katherine, Linette, Wulfhild, Rohesia

- “Medieval Peoples: Titles, Positions, Trades & Classes” (A useful listing of the various titles and positions available in the medieval world. Specific titles are specified by region of origin.)

- “Medieval Society: Peasants, Serfs, Yeomen, and Villeins,” by Skip Knox. (An extremely useful article explaining the different levels of rural commoners.)

- “Medieval Society: The Village,” by Skip Knox. (Again, the same author from Boise State University, this time writing about the lives of working people in medieval Europe.)

You’ll want to make sure that the given name you select is appropriate for the region in which your fief is located, so pay attention to the potential for Germanic, Latin, Celtic, or Norse roots. There’s an excellent site at “Medieval English Names” which might be useful to you, even if your fief isn’t located in England. At any rate, here is a collection of fairly common given names from the 12th and 13th centuries, separated by gender:

Male Names

Adam, Gervase, Gilbert, James, Louis, Ralf, Ademar, Geoffrey, Gerard, John, Walter, Warin, Amaury, George, Bernard, Matthew, Jan, Wulfirc, Alfred, Guy, Nicholas, Lucas, Thomas, Richard, Bernard, Hubert, Aldous, Roger, Simon, Reginald. Charles, Ernis, Henry, William, Percival, Roland

Female Names

Agnes, Agatha, Alice, Avice, Aldith, Astrid, Eva, Beatrice, Elizabeth, Mary, Martha, Philippa, Gilia, Helen, Sybil, Sadie, Lavinia, Isabella, Scholastica, Julia, Margery, Margaret, Molly, Muriel, Joyce, Cecily, Urith, Isolde, Winifred, Grace. Ann, Jane, Katherine, Linette, Wulfhild, Rohesia

Creating a Peasant Paper Doll

In order to complete this assignment, you will need to first draw a generic outline of your peasant. (You may want to use one of these templates if you are not particularly artistically gifted: How to Make Paper Dolls or Ancient History Paper Dolls) Just a note: please equip your paper doll with some fitting undergarments, even if you find articles indicating that not everyone wore them in the 13th century. It’s okay to not be precisely accurate on that count; there’s no need to work on biology right now. Your doll should be drawn on a regular sized sheet of printer paper. You should, on a separate sheet of paper, draw a set of clothing which you could cut out and have your doll wear. (You don’t need to actually cut it out, if you’re afraid you would lose parts of the outfit.) Both your doll and its outfit should be neat, colorful, and hand-drawn (tracing is fine, but NO computer print-outs, please). Your doll and its outfit should have:

Required Elements (Men and Women):

Required Elements (Men):

Required Elements (Women)

You’ll likely find it necessary to do some research on what appropriate clothing looked like, and why peasants wore what they did. Here are some useful sources to help you get started:

Required Elements (Men and Women):

- Appropriate undergarments

- Clothing of a realistic color for your peasant’s social status

- A knife for eating and a cup for drinking, worn at the waist

- Boots, bare feet, or wooden clogs, depending on your fief’s location

Required Elements (Men):

- Overcoat or mantle

- Woolen trousers, stockings, or breeches

- Woolen cap, straw hat, or coif

- Homespun tunic

- Belt or girdle

- Laborer’s apron

Required Elements (Women)

- Wimple or veil for hair (absolutely required for respectable women)

- Wool cape for winter

- Long tunic or dress

- Apron

- Belt or girdle

You’ll likely find it necessary to do some research on what appropriate clothing looked like, and why peasants wore what they did. Here are some useful sources to help you get started:

- “Medieval Clothing and Fabric,” by Melissa Snell. (A quick overview of the basics of medieval clothing.)

- “European Peasant Dress,” by Melissa Snell. (Same author as the above, but this article focuses particularly on what peasants generally wore.)

- “Castle Life: Medieval Clothing.” (A good general article about clothing and sumptuary laws, with several nice illustrations of medieval clothing.)

- “History of Costume: Medieval Period.” (This is the archive of a costume blog, which has some excellent photographs, illustrations, and– best of all– some scanned paper dolls in medieval costumes which you might want to take a look at.)