The year is 1207 CE, and you’re living in the midst of the High Middle Ages– not that you would ever term it as such. To you, this is how the world has always been, and likely always will be: small villages are scattered across the land, and unless you are particularly wealthy, you likely will never travel much more than twenty miles from the place you were born. The rhythm of your life is dictated by the planting seasons and the rituals and observances of the Catholic Church. Your work– no matter what your social station– is hard and constant, interrupted only by observances of holy days. Still, when the harvest is good and there is no war, life is relatively peaceful and orderly.

As a group, you will need to complete the following tasks:

As a group, you will need to complete the following tasks:

- List which of you is going to perform each social role during the course of this activity on your Anatomy of a Fiefdom handout. You will be graded as a group for you performance on fiefdom tasks, and as an individual on individual tasks.

- Familiarize yourself with the key terms of this project. You will need to define– in your own words– the terms listed on your Anatomy of a Fiefdom handout.

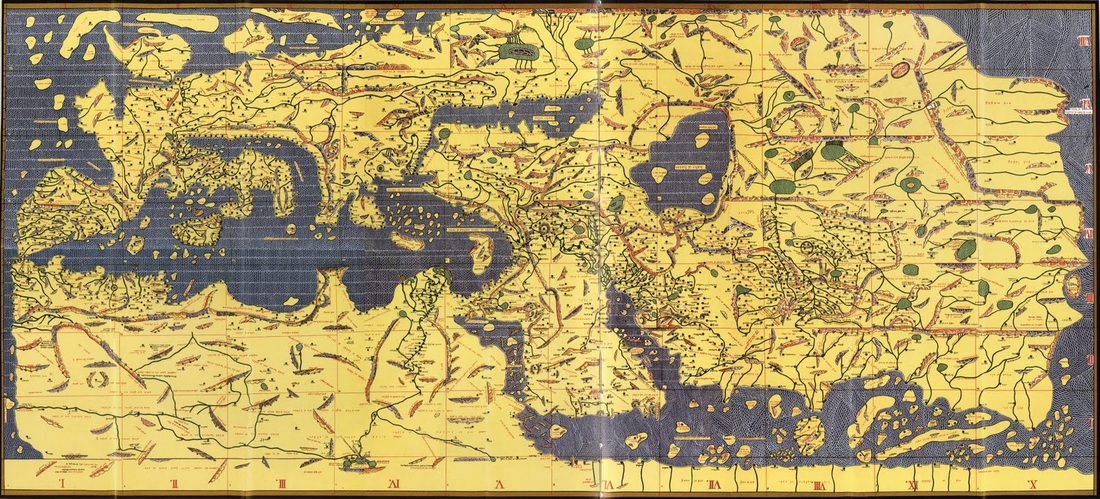

- Familiarize yourself with the geography of medieval Europe and determine where your fiefdom is located. Firstly, identify all of the listed kingdoms and geographic features on the map in your Anatomy of a Fiefdom handout. Then, choose a location for your fiefdom. Is it in England? France? The Holy Roman Empire? Do some research and decide where you’d like to be located. All of your subsequent work should reflect that geographic location. (That is, if you decide that your fiefdom is in northern France, your work as an individual should focus on northern France as well.)

- Name your fiefdom using the resources located below.

- Chose the colors and motto of your fiefdom, again using the resources located below. Remember that your motto should be reflective of the values and world of the 13th century, so please resist the temptation to be anachronistic.

Geography of Western Europe in the High Middle Ages

You’ll find that many maps (including the one on your worksheet) have slightly different borders to various kingdoms during the 13th century. This is due to the fact that there are a number of succession struggles and wars going on in western Europe during this period, which means that borders are generally in flux. You’ll want to consult a variety of sources in order to get a good sense of where various kingdoms are likely located in 1207 CE:

Naming Your Fiefdom

England

Anglo-Saxon villages prior to the Norman invasion in 1066 CE were often named for the chieftain who was in control of the region, which helped to indicate to which tribe the village belonged. These regions usually ended with the suffix “-ing” or “-folk,” with the first part of the name coming from the name of the local tribal leader. By this naming convention, those who lived in the village of Hastings were properly “Haesta’s people,” and those in Reading were “Redda’s people.” After 1066, Anglo-Saxon place names generally referred to local environmental features instead of tribal affiliations– Oxford is, therefore, a place were oxen were driven across a low point in the river (a ford).

Some other useful Anglo-Saxon place name suffixes:

France

Like naming conventions in England, territories in France were usually named for the land-owner as a way of indicating who was in charge in that region. In some cases, names were more descriptive, evoking the terrain in which a village was located. Unlike England, however, French place names had, from a very early date, included many different linguistic influences: Latin, Nordic languages (from Viking contact), and Germanic languages like Anglo-Saxon.

Some useful French place name suffixes:

Holy Roman Empire

Again, Germanic naming conventions in the Holy Roman Empire were very similar to those in France and England, in that they illustrated the ownership of land and the allegiance of the people who lived there, or the geographic characteristics of the region.

Some useful Germanic place name suffixes:

Anglo-Saxon villages prior to the Norman invasion in 1066 CE were often named for the chieftain who was in control of the region, which helped to indicate to which tribe the village belonged. These regions usually ended with the suffix “-ing” or “-folk,” with the first part of the name coming from the name of the local tribal leader. By this naming convention, those who lived in the village of Hastings were properly “Haesta’s people,” and those in Reading were “Redda’s people.” After 1066, Anglo-Saxon place names generally referred to local environmental features instead of tribal affiliations– Oxford is, therefore, a place were oxen were driven across a low point in the river (a ford).

Some other useful Anglo-Saxon place name suffixes:

- -barrow (wood)

- -burh or -burg (town)

- -bury (fortified place)

- -ford (shallow river crossing)

- -ham (village)

- -hurst (wooded hill)

- -mere (lake)

- -port (market town)

- -ton (enclosed village)

- -wick (produce from a farm)

France

Like naming conventions in England, territories in France were usually named for the land-owner as a way of indicating who was in charge in that region. In some cases, names were more descriptive, evoking the terrain in which a village was located. Unlike England, however, French place names had, from a very early date, included many different linguistic influences: Latin, Nordic languages (from Viking contact), and Germanic languages like Anglo-Saxon.

Some useful French place name suffixes:

- -acum (property)

- -ay (property)

- -bosc (wood or forest)

- -chatel (castle)

- -court (farm with a courtyard)

- -mesnil (property)

- -mont (mountain or hill)

- -val (valley)

- -ville (village or town)

Holy Roman Empire

Again, Germanic naming conventions in the Holy Roman Empire were very similar to those in France and England, in that they illustrated the ownership of land and the allegiance of the people who lived there, or the geographic characteristics of the region.

Some useful Germanic place name suffixes:

- -ach (river)

- -bach or -bek (stream)

- -bugh (keep or fort)

- -dorf (village)

- -felde (field)

- -furt (ford)

- -hagen (hedged field or wood)

- -heim (home or village)

- -stadt (settlement)

- -wend (small settlement)

Heraldic Mottos

Mottos were meaningful phrases meant to represent the values or aspirations of the ruling family. Your fief’s motto should reflect the geographic region, and should therefore have roots in either French, German, or Latin. Here are some examples which you can use as a model:

While you’re welcome to use any of the above as inspiration, your motto should be original. As your motto should not be in English, you’ll likely want to use Google Translate if you’re not a student of German, French, or Latin. Do your best to make your motto plausible and appropriate to the time period.

- Celeritar (With speed)

- Disce pati (Learn to endure)

- Fulminis instar (Like lightning)

- Fructo cognoscitur arbor (A tree is recognized by its fruit)

- Fortis in arduis (Brave in difficulties)

- Fide fortuna forti (Faith is stronger than fortune)

- Flead agus fuilte (Celebrate and welcome)

- Fortes fortuna juvat (Fortune favours the bold)

- Inclytus virtute (Renowned for virtue)

- L’homme vrai aime son pays (The true man loves his country)

- Memor esto (Be mindful of thy ancestors)

- Ne timeo nec perfice (I neither fear nor despise)

While you’re welcome to use any of the above as inspiration, your motto should be original. As your motto should not be in English, you’ll likely want to use Google Translate if you’re not a student of German, French, or Latin. Do your best to make your motto plausible and appropriate to the time period.

This awesome project has been adapted from Carol Galloway.